I shall tell you of a wonderful incident in the life of Vachaspati Misra.

His father urged him to marry. Vachaspati understood nothing of marriage. He however, bowed to his father’s wishes, taking it for granted that whatever he said was correct.

Vachaspati was engrossed in the search for God. He understood nothing else. If anyone talked about anything, he took it to be a topic on God.

So when his father asked him, “Will you marry?” he said, “Yes.” Perhaps he thought his father said, “Will you meet God?” and he said yes. Just as it happens with people generally, if a person is seeking wealth and you ask him, “Will you seek religion?” he will think you are asking him about wealth. Whatever the search within, that only rings in our ears. So Vachaspati also heard what was within him perhaps and said yes.

When he was made to sit on the horse to go to the bride’s place he asked, “Where are you taking me?”

His father said, “You fool! Don’t you know you are getting married? Did you not agree to get married?”

So Vachaspati thought it was not right to refuse at that moment. Even though he had agreed without knowing, he took it to be God’s wish that he be married. He returned home with his bride but it never occurred to him that he had brought a bride home!

How could he remember, for it was not he who said yes to marriage, nor he who got married. He was engrossed in his own work. He was writing a commentary on Brahma Sutra.

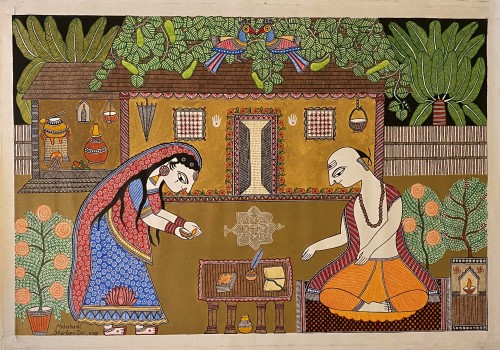

He finished this work after twelve years. For twelve years his wife would quietly light the lamp for him in the evening and place flowers at his feet each morning. In the afternoons she brought his meals and when he finished, she quietly withdrew. For twelve years Vachaspati had not the slightest awareness of his wife. She made no effort to let him know she was there. On the contrary, she took all possible care that he may not, even by mistake, come to know of her presence. She wanted to cause no disturbance in his work.

After twelve years, on the night of a full-moon, when his work was completed and Vachaspati rose to go to bed, his wife picked up the lamp to show him the way.

For the first time Vachaspati (so the story goes) saw his wife’s hand. Now, after twelve years, when his work was over and his mind was disengaged from work. He saw the hands, the bangles and heard the tinkle of her bangles.

He turned round and saw her and he exclaimed, “Woman! What are you doing, alone here at this time of the night? Who are you? From where have you entered, the whole house is closed? Where do you have to go? Shall I reach you home?”

His wife said, “For twelve years, you have been busy with your work. Perhaps you have forgotten – you have been so busy! It is not possible that you should remember.

“If you can think back, twelve years from now, perhaps you may be able to recollect – I am the woman you brought to this house as your wedded wife.”

Vachaspati wept. “It is too late now!” he moaned. “I have already made the vow to leave home once my composition is completed. Now it is time for me to leave! It is almost dawn and I am ready to leave. Why did you not tell me earlier, foolish girl! You should have given me some hint! Now it is too late.” Saying this, he wept like a child.

Seeing her husband cry, she fell on his feet and said, “Whatever I was to achieve, I have achieved through these tears of yours. I wish for nothing more. Go without any compunction. What more could I have achieved than this, that Vachaspati’s eyes are filled with tears for me? I have received more than I deserved.”

Vachaspati named his book Bhamati. This word has nothing to do with the book. It is his wife’s name. He said to her “I can do nothing for you but let the world forget me, let it not forget you. I shall name my book after you.”

It is a fact, no one remembers Vachaspati but Bhamati is remembered by many. Bhamati is a wonderful exposition of the Brahma Sutra. There is none to equal it.

This woman must be having the feminine-mystery. It is my firm belief that she attained so much of Vachaspati in that single moment, as she would never have attained by a thousand other means. The way Vachaspati must have become one with the heart of this woman, no woman could ever establish such oneness with her husband.

The feminine-mystery, the non-presence of this woman, touched the very life-breath of Vachaspati. Twelve years – and this woman did not allow him to feel her presence! And every day she lit his lamp, every day she fed him.

Vachaspati asked, “Then was it you who placed flowers at my feet every morning? And was it you who put the (food) tray before me and was it you who lit the lamp for me every evening? But how is it that I did not ever see your hand?”

Bhamati replied, “If my hand had become visible to you, it would only have meant that my love was lacking, I could wait.”

So it is not necessary that all women obtain this feminine-mystery. This is only a name given by Lao Tzu, for this name is symptomatic, suggestive and enables us to understand this term. A man also can attain this Female-Mystery. Actually, only those who have thus reached this state of prayerful awaiting can establish their identity with Existence.

The door of this feminine-mystery is the original source of heaven and earth.

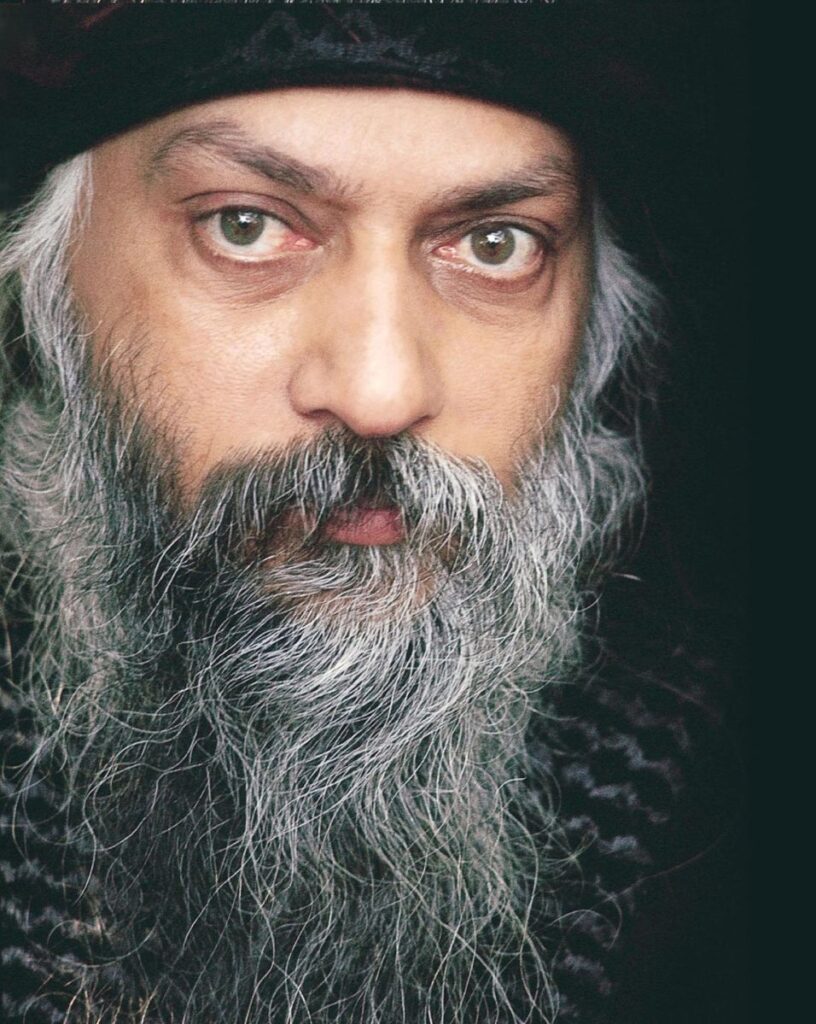

Osho – The Way of Tao Volume 1

Pic courtesy: https://peterzernis.com

Vachaspati Misra was a ninth or tenth century Hindu philosopher of the Advaita Vedanta tradition, who wrote bhashya (commentaries) on key texts of almost every 9th-century school of Hindu philosophy. He wrote so broadly on various branches of Indian philosophy that the later Indian scholars called him “one for whom all systems are his own,” or in Sanskrit, a sarva-tantra-svatantra.

Vachaspati Misra wrote ‘Bhamati’, a commentary on sage Adi Shankaracharya’s Brahma Sutra Bhashya and the Brahmatattva-samiksha, a commentary on his guru Mandana Mishra’s Brahma-siddhi. It is believed that the name of the work ‘Bhāmatī’ was inspired by his devout wife.

The Brahma Sūtra is a Sanskrit text, attributed to the sage Badarayana or sage Vyasa, estimated to have been completed in its surviving form in approx. 400-450 CE, while the original version might be more ancient and composed between 500 BCE and 200 BCE. It is one of three most important texts in Vedanta along with the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, and in fact systematises and summarises the philosophical and spiritual ideas in the Upanishads. Brahma Sutra consists of 555 aphoristic verses (sutra) in four chapters and has greatly influenced various schools of Indian philosophy, though it was interpreted differently by the non-dualistic Advaita Vedanta sub-school, the theistic Vishishtadvaita and Dvaita Vedanta sub-schools as well as others. Adi Shankaracharya’s interpretation of the Brahma Sutra attempted to synthesise the diverse and sometimes apparently conflicting teachings of the Upanishads.

Acharya Rajneesh (1931-1990), known later as Osho, was an Indian godman, philosopher, mystic and founder of the Rajneesh movement. He was viewed as a controversial religious leader during his life. He rejected institutional religions, insisting that spiritual experience could not be organised into any one system of religious dogma. He advocated meditation and taught a unique form called dynamic meditation. Rejecting traditional ascetic practices, he asked his followers to live fully in the world but without attachment to it. Pic courtesy: https://www.sannyas.wiki/