One day, while walking through the streets of Varanasi (Benares), Adi Shankaracharya, India’s celebrated Vedic scholar, philosopher and teacher of the 8th century, encountered a chandala (an untouchable) carrying a load of dead animals.

The chandala asked Shankaracharya to move aside, saying:

“Move, O Brahmin, move! I am polluted, and my touch will defile you.”

Taken aback by the chandala’s words, Shankaracharya replied:

“You may be carrying polluted flesh, but I am carrying the pollution of ignorance. Who is more polluted, you or I?”

The chandala, impressed by Shankaracharya’s humility, asked:

“How can one like you, who has realised Brahman, be polluted?”

Shankaracharya replied:

“As long as one identifies with the body, one is bound by ignorance. Only when one realises the Self beyond the body can one attain liberation.”

The chandala, moved by Shankaracharya’s words, prostrated before him and asked:

“Who are you, O revered one?”

Shankaracharya revealed his identity and took the chandala as his disciple.

This one anecdote illustrates Shankaracharya’s humility and his emphasis on spiritual growth and self-realisation as the ultimate goal in life. Despite being a renowned scholar, he acknowledged his own limitations and demonstrated the illusory nature of social distinctions. By advocating the pursuit of knowledge and self-realisation, Shankaracharya challenged those who emphasised external rituals over inner spirituality.

Born into a devout Brahmin household in Kaladi, Kerala, Shankara (788-820 CE?) had his early education in traditional Vedic studies. Initiated into sannyasa (a life of renunciation) by Govinda Bhagavatpada, he undertook extensive studies of ancient Hindu scriptures under his guru and other renowned teachers. Thereafter, he travelled extensively, participating in debates and discussions on philosophy with eminent scholars and heads of various religious sects, and visiting major pilgrimage centres, including Kashi, Gaya and Badrinath.

As a student of the prasthana trayi* (three canonical sources of Hinduism, the Upanishads, the Bhagavadgītā and the Brahma Sutras), which are the foundational scriptures of Vedanta (Vedic-Upanishadic philosophy), Shankaracharya propounded and expanded upon several key philosophical concepts of Hinduism, especially Advaita Vedanta (non-dualistic philosophical tradition):

- Brahman: Ultimate reality, unchanging and all-pervading

- Atman: Individual self, ultimately identical with Brahman

- Maya: Illusion or ignorance obscuring the true reality of Atman and Brahman

- Moksha: Liberation from the cycle of birth, death and re-birth by transcending maya and realising the unity of Atman with Brahman

With these key concepts as the foundation, Shankaracharya wrote 18 commentaries on major scriptural texts and authored 23 books on the fundamentals of the Advaita Vedanta philosophy, which expound the principles of the non-dual Brahman. He also composed over 70 devotional and meditative hymns like Soundarya Lahari, Sivananda Lahari, Nirvana Shatakam, Sri Dakshinamurti Stotram, Maneesha Panchakam, etc.

Among his seminal contributions to the Hindu religion and philosophy are:

- Commentaries on 12 major Upanishads (ancient Indian philosophical treatises appearing at the end of the four Vedas) with Advaitic interpretations

- Commentary on sage Badarayana’s Brahma Sutras (or Vedanta Sutras), a Sanskrit text which synthesises and harmonises Upanishadic ideas and practices

- Commentary on the Bhagavad Gita (The Song of God) from an Advaita perspective

- Vivekachudamani (Crest Jewel of Discrimination), a comprehensive poetic guide to spiritual growth and self-realisation

- Upadeshasahasri (A Thousand Teachings), a good introduction to Shankaracharya’s philosophy

With his voluminous literature of bhashya-s (commentaries), prakarana-s (treatises), devotional hymns, verses and stotra-s (psalms) ‘culled out from the garden of the Upanishads,’ Shankaracharya shaped Indian thought and philosophy in a fundamental way, contributing to Hindu resurgence and identity. He is credited with unifying Indian thought by integrating its diverse philosophical traditions, and with promoting Sanskrit education.

Adi Shankaracharya was known to reconcile various Hindu sects – Vaishnavism, Shaivism and Shaktism – with the introduction of the Pañchāyatana form of worship, the simultaneous worship of five deities – Ganesha, Surya, Vishnu, Shiva and Devi – arguing that all deities were different forms of the one Brahman.

During his extensive travels, Shankaracharya established four amnaya matha-s (traditional Hindu monasteries) in the four corners of the country, at Sringeri (Karnataka), Dwaraka (Gujarat), Puri (Odisha) and Jyotirmath (Uttarakhand), entrusting each with a Veda and a philosophical tradition. Their foundation and able stewardship by an illustrative lineage of learned disciples till today had a significant role in the development of his teachings into the leading philosophy of India.

A philosopher-poet-saint-scholar-teacher with stupendous achievements in multiple arenas, Shankaracharya lived only for a short span of 32 years.

However, he had many disciples and followers who continued and elaborated his work, notably the 9th-century philosopher Vachaspati Mishra. The extensive Advaita literature continues to influence and inspire modern Hindu thought.

Shankaracharya’s scholarship and intellectual rigour, his poetic splendour and spiritual humility, and his role in unifying Indian thought inspired several Western philosophers like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. His extensive work continues to engage many Indic scholars from across the world even today.

More anecdotes

Here are more anecdotes about Adi Shankaracharya:

Once, Shankaracharya, accompanied by his disciples, was walking along a street in Varanasi, when he came across an old-aged scholar reciting the rules of Sanskrit grammar. Taking pity on him, Shankaracharya went up to the scholar and advised him not to waste his time on grammar at his age, but to turn his mind to God in worship and adoration, which only would save him from this vicious cycle of life and death. The hymn Bhaja Govindam is said to have been composed on this occasion. This composition proves that Shankaracharya, who is often regarded as the reviver of the Jnana Marga or the “Path of Knowledge” of Hinduism to attain mukti (salvation), was also a proponent of the Bhakti Marga or the “Path of Devotion” to attain the same goal. For many scholars, this composition encapsulates with both brevity and simplicity the substance of all Vedantic thought found in the works of Shankaracharya.

A boatman once asked Shankaracharya for the ferry fare. Shankaracharya replied, “I have no money.” The boatman said, “Then pay me with your knowledge.” Shankaracharya shared his wisdom, and the boatman became his disciple.

Padmapada, a devoted disciple, was initially a thief. Shankaracharya transformed him through spiritual guidance, and he became one of Shankaracharya’s most trusted disciples.

Shankaracharya is believed to have composed Vivekachudamani, a poem on spiritual discernment, after encountering a group of seekers asking for guidance.

* In Prasthana Trayi:

- Upanishads represent Shruti – Revealed knowledge, divine revelation.

- Bhagavad Gita represents Smriti – Remembered tradition, authoritative scripture.

- Brahma Sutras represent Nyaya or Yukti – Logical reasoning, philosophical systematisation.

This trilogy provides:

- Comprehensive understanding: Integrating revelation, tradition and reason.

- Holistic approach: Balancing faith, intellect and spiritual growth.

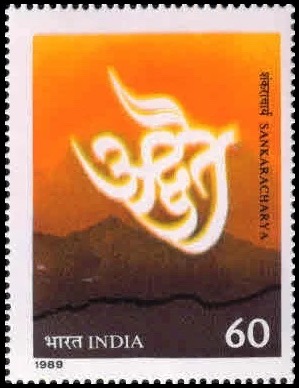

Image 1 above: A postage stamp issued by India post on April 28, 2020 to commemorate Adi Shankaracharya Jayanti.

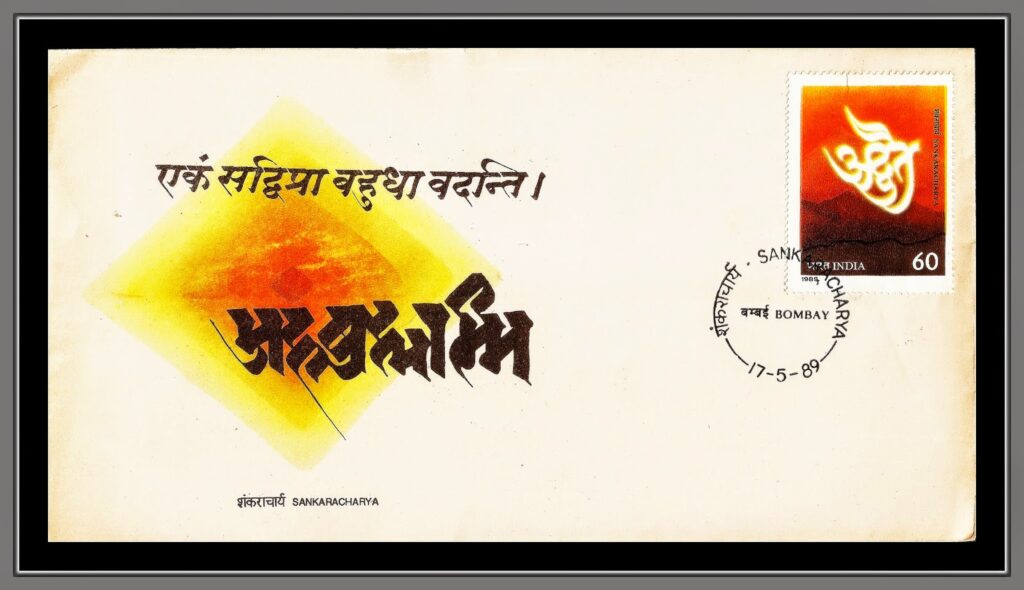

Image 2 above: The first day cover issued on the above occasion. Both images courtesy The Sanskrit Philatelist.

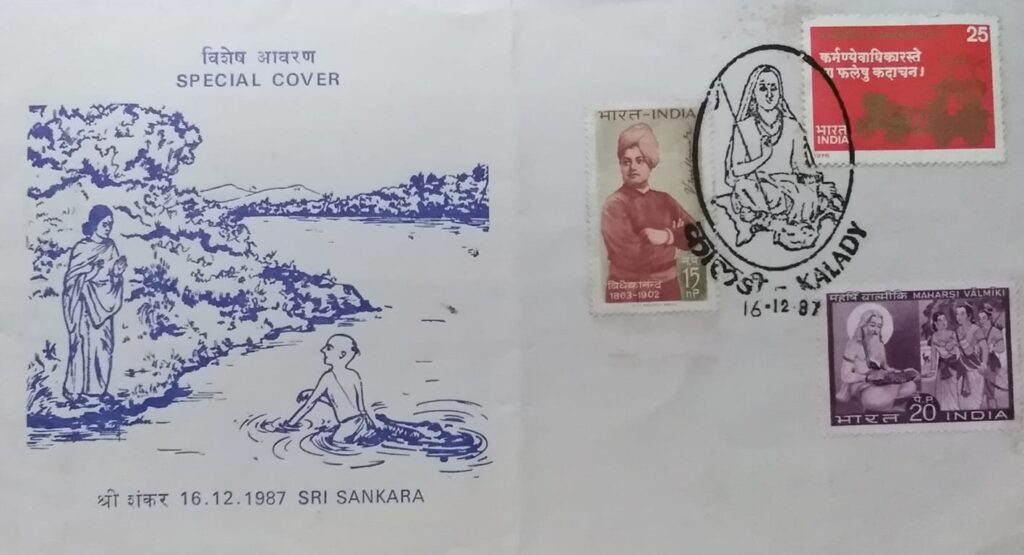

Image: A special cover of Sri Adi Shankaracharya issued on the occasion of the inauguration of permanent pictorial cancellation on Dec. 16,1987 at Kalady, Ernakulam, Kerala. Courtesy https://www.facebook.com/groups/panindiapostal/posts