On a September morning in 1928, Alexander Fleming sat at his work bench at St. Mary’s Hospital after having just returned from a vacation at The Dhoon (his country house) with his family. Before he had left on vacation, Fleming had piled a number of his petri dishes to the side of the bench so that Stuart R. Craddock could use his work bench while he was away.

Back from vacation, Fleming was sorting through the long unattended stacks to determine which ones could be salvaged. Many of the dishes had been contaminated. Fleming placed each of these in an ever-growing pile in a tray of Lysol.

While sorting through his pile of dishes, Fleming’s former lab assistant, D. Merlin Pryce, stopped by to visit with Fleming. Fleming took this opportunity to gripe about the amount of extra work he had to do since Pryce had transferred from his lab. To demonstrate, Fleming rummaged through the large pile of plates he had placed in the Lysol tray and pulled out several that had remained safely above the Lysol. Had there not been so many, each would have been submerged in Lysol, killing the bacteria to make the plates safe to clean and then reuse.

While picking up one particular dish to show Pryce, Fleming noticed something strange about it. While he had been away, a mold had grown on the dish. That in itself was not strange. However, this particular mold seemed to have killed the Staphylococcus aureus that had been growing in the dish. Fleming realized that this mold had potential.

Fleming continued to run numerous experiments to determine the effect of the mold on other harmful bacteria. Surprisingly, the mold killed a large number of them. Fleming then ran further tests and found the mold to be non-toxic.

Fleming was not a chemist and thus was unable to isolate the active antibacterial element, penicillin, and could not keep the element active long enough to be used in humans. In 1929, Fleming wrote a paper on his findings, which did not garner any scientific interest.

Though Fleming discovered penicillin, it took Australian Howard Florey and Ernst Chain to make it a usable product.

Fleming had no idea that penicillin would someday lead to a revolution in medicine. It was not for fifteen years that the nature and importance of penicillin was understood. Ernst Chain (1906-1979) and Howard Florey (1898-1968) came to work at Oxford in the 1930s and began to work with antibiotic substances. Eventually, they were able to identify and purify penicillin, which made it available for use as a drug. Together, Fleming, Chain, and Florey shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in medicine for their discovery.

The discovery of penicillin and sulfanilamide drugs in the 1930s played a major role in treating bacterial diseases and in the creation of today’s pharmaceutical industry. These chemical agents, called antibiotics, saved many lives during World War II.

The effect of sulfas and penicillins on stopping diseases, infections, and their spread was electrifying. There had previously been no compound or medicine that could prevent the diseases caused by bacteria. Only after a connection was made between living cells and chemical components was it possible to produce these new medicines. Sulfas were demonstrated to be instrumental in saving many lives, and scientists finally did produce a penicillin, administered by mouth, that was used to treat soldiers during World War II. Because of their rapid effectiveness, a great deal of publicity was given to these drugs. This high visibility caused them to be hailed as “miracle drugs.”

Source: www.encyclopedia.com

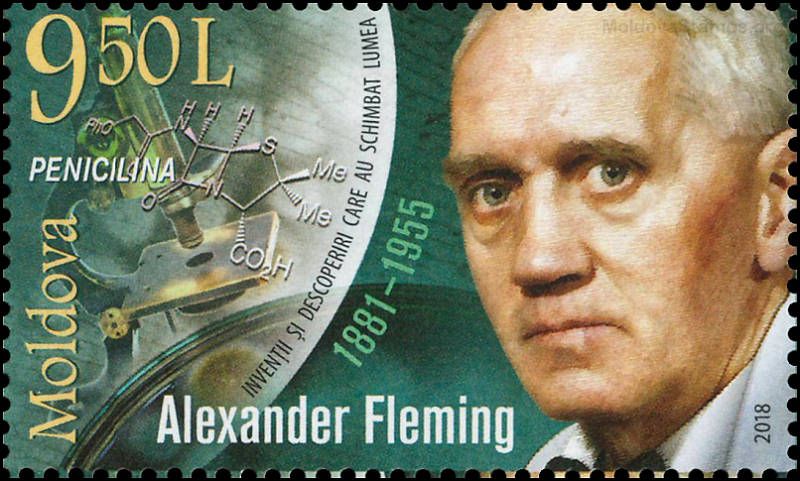

Image above: Moldova celebrated the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming with a postage stamp issued in 2018. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Image below: This stamp on penicillin issued in Great Britain in 1967 was part of a set depicting great British discoveries. The other stamps showed radar, television and the jet engine. Courtesy: https://www.baus.org.uk/