There are several stories and legends surrounding Bodhidharma. Some of them may be real; and a lot others just made up. In any case, they are very interesting. They bring forth the down-to-earth wisdom and the curt wit of Bodhidharma.

It is said; legends amplify facts and render them in a way they become more significant and larger in scope. This holds good for some of the stories associated with Bodhidharma. They might have sprung using him as the ideal prop to symbolise the essence of Zen. All these stories are placed in the context of the master-disciple relationship. In these stories, Bodhidharma stands for an ideal and an unreachable model; and a stern but loving teacher who guides his disciples unerringly to awakening.

With these, Bodhidharma introduced to China an alternative to text-based scholastic learning. He was the first to proclaim: “Directly point to the human mind; see one’s nature and become a Buddha; do not establish words and letters.”

Like all legends, the stories of Bodhidharma too try to say something new and unexpected. They can be enjoyed as stories and one can also read meaning into them to extract a teaching:

According to the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, around the year 527 (?) the eighth year of Putong, Bodhidharma called on Emperor Wu Ti (502-550 AD) of Liang dynasty, a fervent patron of Buddhism. The emperor was then at Jinling (today’s Nanjiang).

Emperor Wu asked Bodhidharma: “After I ascended the throne, I have built countless temple residences for monks and had innumerable scriptures copied (from Pali and Sanskrit to Chinese). How much merit have I accrued?”

Bodhidharma replied: “There is no merit.”

Startled, the emperor then asked Bodhidharma: “What is the first principle of the holy teachings?”

Bodhidharma replied: “Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”

The emperor, frustrated, then asked Bodhidharma: “Who is this that stands before me?”

Bodhidharma answered: “I don’t know.”

The emperor did not understand what Bodhidharma was saying. He was disappointed and upset. The meeting was obviously unsuccessful. Thereafter, Bodhidharma moved north, crossing the Yangtze River.

Years later Emperor Wu realised that he was hasty in dismissing Bodhidharma; and with regret wrote an inscription, on hearing of the death of the sage:

Alas…! I saw him without seeing him. I met him without meeting him. I encountered him without encountering him. Now as before I regret this deeply...!

[This exchange between Bodhidharma and the Emperor later became the basis of a koan in Zen. It points out that we all fall into the trap of expecting our accomplishments to be acknowledged and honoured. Tomes have been written on Bodhidharma’s replies to the emperor: “Vast emptiness, nothing holy” and “I don’t know.”]

*****

It is said, once, as Bodhidharma was walking along a street, a parrot called out to him.

The parrot could talk. It said:

Mind Come from the West,

Mind Come from the West,

Please teach me the way

To escape from this cage.

Bodhidharma thought, ‘I came here to save people and it’s not working out; at least I can save this parrot.’ And so he taught the parrot:

To escape from the cage,

Stick both legs straight out.

Close both eyes tight.

That’s the way to escape your cage.

The parrot heard it and understood. It pretended to be dead. It lay on the bottom of its cage with its legs stuck out still and its eyes closed tight, not moving, not even breathing. The owner found the parrot this way and took it out to have a look. He held the bird in his hand, peering at it until he was convinced it was indeed dead. The only thing about it was, its body was still warm. But it wasn’t breathing. And so the owner opened his hand and in that instant the parrot flew away and escaped its cage.

[“Bodhidharma coming from the West” became a much-discussed Zen phrase; and came to be regarded as the “essence of Zen.” In another interpretation, the parrot was consciousness, cage the body and the teaching was to be free from the bonds of physical limitations and go beyond the demands of the body.]

*****

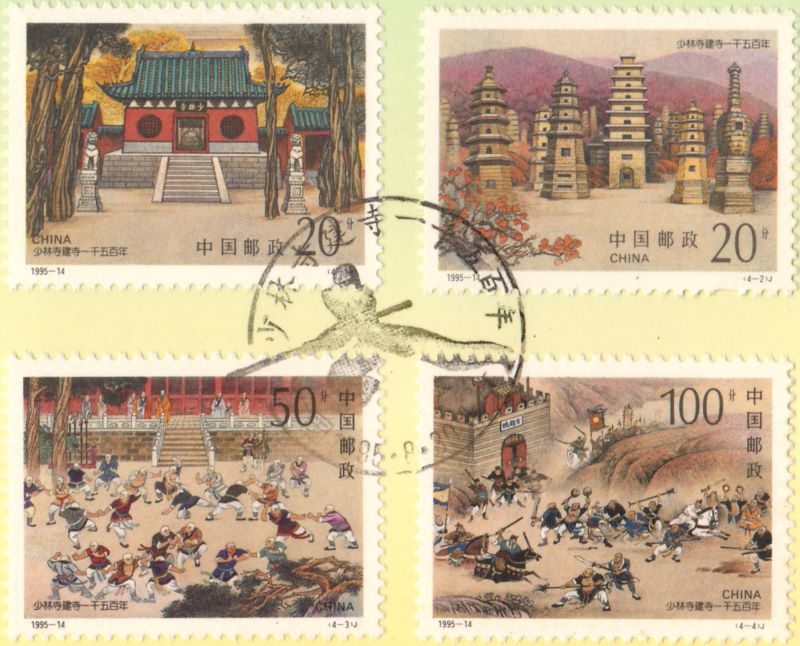

After travelling and teaching around the country, Bodhidharma settled at Shaolin (Shorinji), a monastery on the Hao-shan mountain near Loyang, in what is now Honan province.

Legend has it that Bodhidharma remained seated in meditation in front of the wall of the Shaolin Monastery for nine years. While Bodhidharma was meditating, according to the legend, he became sleepy, and his eyelids grew heavy. In frustration, he tore off his eyelids and threw them on the floor, where they became the first tea plants—used from that time as a mild stimulant. Later, tea-drinking became a habit among the Zen practitioners, to keep awake. It also grew into the aesthetic tea-ceremony.

That wall-gazing was called “Pi-kuan.” The Shaolin temple where Bodhidharma meditated for many years and achieved enlightenment has preserved a large rock on which, it is said, one can see the shadow of the sage – apparently it burned into the rock.

*****

One of Bodhidharma’s disciples among the Shaolin monks was Shen–kuang. One day, Bodhidharma asked Shen–kuang why he continued to turn to him for teachings, reprimanding him that true enlightenment is not sought through the teachings of another, but from within.

Shen–kuang said, “My mind is in pain and is restless. Please, Patriarch, quiet my mind.”

“Find your mind.” said Bodhidharma. “Give it to me, and then I will quiet it and you will feel no pain.”

Shen–kuang searched but couldn’t find his mind. After some hesitation, he said to Bodhidharma, “Master, I can’t find my mind.”

“See, how well I have quieted your mind.” said the Patriarch. Hearing this instruction Shen–kuang understood the meaning of transmitting the Dharma.

With that transmission of the Dharma, Shen–kuang received a new name. It was Hui K’o, “Able Wisdom,” meaning that his wisdom was abundant. Hui K’o later succeeded Bodhidharma as the second patriarch of the Cha’n school; and as the 29th master of Buddhism, in direct line from the Buddha himself.

[The issue that Hui K’o brought up was the restlessness of his mind. But there has to be a mind in the first place. There is no mind; it is only a bunch of thoughts floating like clouds in the sky. The mind has no existence of its own. In other words, it is a false issue.]

*****

There are a number of stories illustrating Bodhidharma’s teaching methods. He often used common objects in instructing students. He would often point at something and ask: “How do you call this?” He would do this using every available object, often switching the names in formulating a question.

For instance, the Master would hold up a staff and ask: “Where do you think I got this? If you call this a staff, you are one whose eyes do not see. If you say it is not a staff, you must be one with no eyes.”

When a monk came to attend on him, the master pointed at the fire and said: “This is fire. But you cannot call it ‘fire,’ for I just did.” The monk could not answer.

The Master would hold up his hand and ask “What is this?”

[The naming game, as it is called, is authentically Cha’n; and attributed to Bodhidharma. There are no correct or wrong answers here. It is in the way one reacts; and it is also contextual.

The idea appears to be that he who knows will know how to answer the question without breaking the rule (e.g., one must not speak and yet must not keep silent). Further, if things are empty of that which makes a real thing real, then names do not refer. If they do not refer, then you violate the Buddhist teaching of emptiness. Therefore, one’s ability to find a way out of the dilemma is taken to be a sign of one’s understanding of the Chan teaching. The answers could come in a wide variety, ranging from simple verbal responses to acrobatics.

A person may relate to what he/she believes in one of two ways: the notional way and the direct way. If a person understands it in a notional way, he will see only the verbal symbols of the proposition. On the other hand, a person who understands a proposition in the direct sense would be capable of answering semantic questions relating to the proposition as well as other types of questions.

So what is the appropriate way to handle the relationship between a name and the named? It seems that an all-or-nothing attitude is not the right approach. Instead, whether one has acted appropriately in using (not using) some bits of language are the issues to be decided by the teacher, depending on the context and the way the student reacts.

Answering that question, no doubt, is a daunting task.]

*****

Once, Bodhidharma presented an imprint of a beautiful lotus flower in brown sugar to a disciple. The disciple admired the imprint but would not eat it. The master then took the imprint, broke it into pieces, gave it back to the disciple and asked him to eat it. The disciple ate the pieces and enjoyed it.

The master explained, “Your studies are like this imprint of a lotus flower. You can hold it and admire it but you cannot enjoy it until you break it and put it in your mouth. Scholarship is a form and it should be brought into your experience by meditation. The purpose of all learning is to help meditation.”

[That was to illustrate that book-learning and meditation, each has its value. Book learning is no substitute for personal experience.]

If you know that everything comes from the mind, don’t become attached. Once attached, you’re unaware. But once you see your own nature, the entire canon becomes so much prose. Its thousands of sutras and shastras only amount to a clear mind. Understanding comes in mid-sentence. What good are doctrines? The Ultimate Truth is beyond words. Doctrines are words. They’re not the Way. The Way is wordless. Words are illusions… Don’t cling to appearances, and you’ll break through all barriers.

*****

The martial arts of the Shaolin temple, the weapon-less fighting that later evolved into kung fu (gong fu) traces its origin and inspiration to Bodhidharma.

When Bodhidharma arrived, the Shaolin temple was primarily a monastery for translator-monks who pored over Sanskrit and Pali texts to translate them into Chinese. By overdoing their task, the monks had grown physically weak; and some had even hunched. They were too weak to defend themselves against robbers who frequently attacked the monastery for food-grains. They had also grown feeble in mind, and therefore, were not progressing in meditation.

Bodhidharma impressed on the monks the need to be strong both in body and mind. He prescribed them a set of physical exercises, based on Indian yogic practices, which strengthened their bodies and calmed their minds, allowing them to meditate with more resolve.

Bodhidharma’s primary concern was to make the monks physically strong enough to withstand both their isolated lifestyle and the deceptively demanding training that meditation requires. Nonetheless, the techniques he taught also served as an efficient fighting skill. It is said, Bodhidharma initially trained the monks in the ancient Indian style of armless combat, which used mainly punching and fist techniques. It was called Vajramushti (diamond-fist) which he, as a prince, learnt in India. With that, the Shaolin style of fist fighting ch’uan-fa (literally “way of the fist”) was founded.

His system of movements combined artistic and acrobatic styles; and used circular principles to redirect an opponent’s attack. Though those movements were slow and cautious, they were a form of strength. The theory behind it was to always be on guard by using the attacker’s energy and redirecting it back to him in a circle. These circular techniques, sometimes called “arcs”, allowed a student to yield to an opponent’s thrust, ultimately forcing the opponent to become unbalanced and vulnerable to multiple counters. This style was practiced as exercise and as a form of meditation.

Bodhidharma’s style was eventually formalised into the martial arts style known as the Lohan (Priest-Scholar). It contained eighteen positions and hand movements. It was the basis of Chinese Temple Boxing and the Shaolin Arts, a powerful and well-known system of hand-fighting.

The Bodhidharma style did not, perhaps, include (open) empty-hand fights. According to legend, the eighteen positions which he introduced were further improvised and enhanced to 170 positions decades after his death by two Shaolin monks: Ch’ueh Yuan and Li-shao. This was the basis for kung fu, which is now probably the best known of all Asian unarmed martial arts.

The ground rules of martial arts were laid down by Bodhidharma. He prescribed that martial arts should never be used to hurt or injure needlessly. In fact, it is still one of the oldest Shaolin axioms that ‘one who engages in combat has already lost the battle.’

His Five Commandments condemned killing, robbery, obscenity, telling lies and drinking wine. Meat eating was considered “not necessary”; but there was no commandment against that. Hundreds of years later, the emperor gave the monks meat to eat and wine to drink. This was known as “The Change of the Sixth Ancestor”. Silence was highly prized and to be strived for.

Thus, the system crafted by Bodhidharma by integrating yoga for self-discipline and martial arts for self-defence gave rise to a system that was at once spiritual and combative; the kung-fu. Monks of the Shaolin Temple who specialised in kung fu have continued teaching Bodhidharma’s techniques since 539 CE.

The Shaolin temple’s claim to fame came from its association with the philosophy of Cha’n. When Cha’n travelled to Japan it came to be known as Zen. Bodhidharma’s concept that spiritual, intellectual, and physical excellences are an indivisible whole necessary for enlightenment fired the imagination of the Samurai warriors. And they made Zen their way of life.

*****

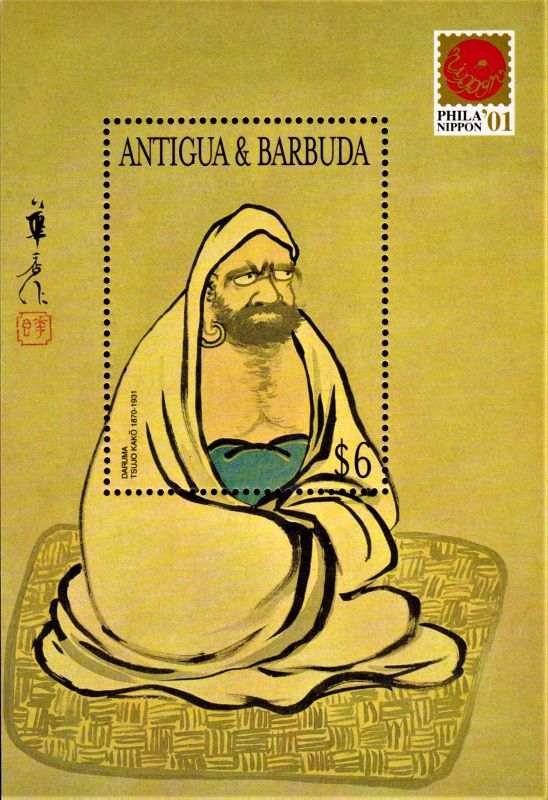

Bodhidharma’s life has become the stuff of fables and legends. His stories and legends have been immortalised over the centuries in a variety of ways, on scrolls, wood block prints, metal, papier-mâché, plastic, etc. His image is easily recognised – a thick rounded body swaddled in robes, with heavy jowls, thick bushy eyebrows, and a beard that frame large round eyes that captivate. When asked how long it took to paint a portrait of Daruma, the great Zen artist Hakuin replied, “Ten minutes and eighty years.”

Bodhidharma has become a popular icon of Japanese culture, folklore, and politics as Daruma (Dharma – short name for Bodhidharma). There is even a Daruma temple at Kataoka, near Horyuuji.

In Japan today, one of the most popular talismans of good luck is the armless, legless, and eyeless Daruma doll, or tumbler doll. Sold at temple festivals and fairs, such dolls are typically painted red, and depict Bodhidharma seated in mediation. When knocked on its side, the doll pops back to the upright position (hence “tumbler” doll, or “okiagari koboshi), “falling seven times and rising eight times.” (nana korobi ya oki), symbolising perseverance through life.

At New Year time, many Japanese individuals and corporations buy a Daruma doll, make a resolution, and then paint in one of the eyes. If, during the year, they are able to achieve their goal, they paint in the second eye. Many politicians, at the beginning of an election period, will buy a Daruma doll, paint in one eye, and then, if they win the election, paint in the other eye. At the year end, it is customary to take the Daruma doll to a temple, where it is burned in a big bonfire.

These Daruma dolls are also believed to protect children against illnesses such as smallpox and to facilitate childbirth, bring good harvests, ensure healthy rearing of silkworms, and generally bring prosperity to their owners.

The story of Bodhidharma is truly remarkable. It is amazing how the legend and the glory of the austere patriarch hailing from Kanchipuram, deep South in India, travelled to the courts of the emperors and the monasteries in China, to the Zen schools and temples in Japan and the world over. He brought awakening and enlightenment to millions of followers; gave a new dimension and a meaning to life, learning and to martial arts. He even became a tumbling doll, a fertility saint, a talisman, a protector of children and a harbinger of good fortune. Bodhidharma is truly a many splendored adorable sage.

Courtesy: AS Sreenivasa Rao blog (https://sreenivasaraos.com)

Bodhidharma (383-531 CE) was a revered Indian Buddhist monk, meditation teacher, and founder of Cha’n Buddhism in China (Zen in Japan).

Life and legacy:

- Born in southern India, possibly in the kingdom of Pallava.

- Left India for China around 475 CE, traveling via the Silk Road.

- Arrived in China during the Liu Song dynasty (420-479 CE).

- Initially rejected by Emperor Wu of Liang

- Meditated for nine years facing a wall in a cave near Shaolin Temple.

- Founded the Cha’n (Zen) school of Buddhism, emphasizing meditation and direct experience.

Teachings:

- Emphasized mindfulness and meditation (dhyana) over scriptural study.

- Introduced the concept of “non-thinking” or “no-mind” (wu nian).

- Focused on the attainment of enlightenment through personal experience.

- Rejected ritualistic and ceremonial practices.

- Encouraged physical exercise and martial arts for spiritual development.

Shaolin connection:

- Bodhidharma is said to have taught meditation and martial arts to Shaolin monks.

- The famous Shaolin Temple, a centre for Buddhist learning and martial arts, became associated with Bodhidharma.

- His teachings influenced the development of Shaolin Kung Fu.

Iconic legends:

- Crossed the Yangtze River on a reed.

- Cut off his eyelids to stay awake during meditation.

- Had a famous encounter with Emperor Wu

Influence:

Bodhidharma’s teachings spread throughout East Asia, influencing:

- Chinese Buddhism

- Japanese Zen Buddhism

- Korean Seon Buddhism

- Martial arts and spiritual disciplines

Texts attributed to Bodhidharma:

- The Two Entrances and Four Practices

- The Bloodstream Sermon

Depictions:

Bodhidharma is often depicted in art as:

- A bearded, robed monk

- Meditating facing a wall

- Holding a staff or fly whisk

- With an intense expression

Bodhidharma’s legacy continues to inspire spiritual seekers, martial artists and philosophers worldwide.

Image 1: A postage stamp issued by China in 2007 depicts Bodhidharma, credited as the transmitter of Cha’n Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch.

Image 2: A postage stamp issued by Antigua and Barbuda in 2001 to commemorate Philanippon ’01 international stamps exhibition in Japan depicts Bodhidharma, famous as Daruma in Japan.

Image 3: Postage stamps issued by China in 1995 featuring the main gate of Shaolin Temple, the forest of dagobas, murals showing the monks practicing martial arts and also the monks rescuing the King of Qin.

Image 4: A postage stamp issued by Japan on New Year Day 1955 features a daruma doll.

Images 1, 2 & 3 courtesy World Buddhist Stamps e-Gallery. Image 4 courtesy Wikimedia Commons.